Phase 1: Landscape overview

Ureteral Stent: Concept

An antimicrobial ureteral stent, which inhibits encrustation and bacterial colonization while maintaining patient comfort.

- Ureteral stent: resists migration, resists fragmentation, is kink resistant and radiopaque.

- Bacterial colonization: antimicrobial activity for up to two weeks.

- Patient Comfort: stent has a low coefficient of fiiction (value) for ease of insertion and will soften on implant at body temperature to maintain patient comfort.

Background

Ureteral stents are used in urological surgery to maintain patency of the ureter to allow urine drainage from the renal pelvis to the bladder. These devices can be placed by a number of different endourological techniques. They are typically inserted through a cystoscope and may also be inserted intraoperatively. Indwelling ureteral stents help to reduce complications and morbidity subsequent to urological and surgical procedures. Frequently, ureteral stents are used to facilitate drainage in conjunction with Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL) and after endoscopic procedures. They are also used to internally support anastomoses and prevent urine leakage after surgery. Ureteral stenting may almost eliminate the urological complications of renal transplantation.

The advent of ESWL and the more recent barrage of endourological techniques have increased the indications for ureteral stents (Candela and Bellman 1997). Indications for use include:

- Treatment of ureteral or kidney stones

- Ureteral trauma or stricture

- Genitourinary reconstructive surgery

- Hydronephrosis during pregnancy

- Obstruction due to malignancy

- Retroperitoneal fibrosis

The need for ureteral stents range from a few days to several months. For patients with serious urological problems, ureteral stent maintenance may become a life-long necessity. Unfortunately, there are many problems associated with using ureteral stents.

Ureteric stenting difficulties

| Common | Rare |

|

|

Today, elastomeric materials, such as silicones, polyurethanes and hydrogel-coated polyolefins are used, with no clear winner, which can withstand the urinary environment.

- Although silicone has better long-term stability than other stent materials, its extreme flexibility makes it difficult to pass over guidewires and through narrow or tortuous ureters.

- Polyethylene is stiffer and easier to use for patients with strictures; however, it has been known to become brittle with time leading to breakage and is no longer commercially available. * Polyurethane has properties that fall in between polyethylene and silicone; however, stent fracture also has been an issue with polyurethanes.

Attempts have been made to develop polymers with a combination of the best of all properties. The key players are C-Flex (Concept Polymer Technologies), Silitek and Percuflex (Boston Scientific).

- C-Flex is proprietary silicone oil and mineral oil interpenetrated into a styrenelolefin block copolymer with the hope of reduced encrustation.

- Silitek (Medical Engineering Corporation) is another silicone-based copolymer.

- Percuflex is a proprietary olefinic block copolymer.

Metallic stents have been used recently to treat extrinsic ureteric obstructions. The effect of synthetic polymers on the urothelium of the urinary tract seems to be dependent on the bulk chemical composition of the polymer, the chemical composition of its surface, coatings on the device surface, smoothness of the surface and coefficient of friction.

Typically, most ureteral stents are made of relatively smooth catheters. Koleski et al., (2000) tested a longitudinally grooved ureteral stent made by Circon in the pig ureter. The results indicated that the grooved stent led to better drainage than a conventional stent. Their opinion is that the ureter wall has a better chance of collapsing over a smooth surface than a grooved surface, especially when debris is present. Stoller (2000) had the same experience with the SpiraStent(Urosurge Corp.). This helical stent was superior at passing stones than a conventional smooth stent.

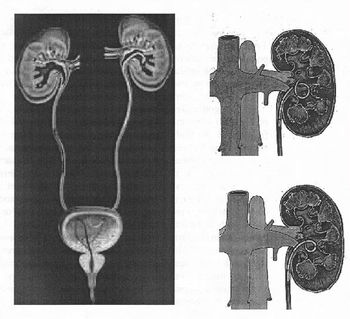

There are a variety of ureteral stent configurations with different anchoring systems. Most stents today have a double pigtail anchoring system. (Tolley, 2000), Dunn et al, (2000) conducted a randomized, single-blind study comparing a Tail stent (proximal pigtail with a shaft which tapers to a lumenless straight tail) to a double pigtail stent. The Tail stent was found to be better tolerated than the double-pigtail concerning lower urinary tract irritative symptoms. A double-J ureteral stent and a flexible ureteropyeloscope are shown in the first diagram. The other two diagrams show a pigtail ureteral stent in place; the end of the pigtail is facing away fiom the ureteral opening in the second of these two diagrams.

Early adverse effects of ureteral stenting include lower abdominal pain, dysuria, fever, urinary frequency, nocturia and hematuria. Patient discomfort and microscopic hematuria happen often. Major late complications include stent migration, stent fragmentation or more serious hydronephrosis with flank pain and infections.

Late complications occurred in one third of the patients in a prospective study using both silicone and polyurethane double pigtail stents (110 stents) in 90 patients. Stent removal was necessary in these patients. Others also have found this percentage of late complications. Device-related urinary tract infection and encrustation can lead to significant morbidity and even death and are the primary factors limiting long-term use of indwelling devices in the urinary tract. Microbial biofilm and encrustation may lead to stone formation. This is typically not a problem when stents are used for short-term indications. Problems of biofilm formation, encrustation and stent fracture occur in patients with long-term indwelling stents.

Typically, manufacturers advise periodic stent evaluation. Cook polyurethane stent removal is recommend at 6 months and 12 months for silicone (Cook product literature). However, stents that are intended for long-term use are usually changed at regular intervals, as frequently as every 3 months.

Forgotten stents are a problem. Monga et al., 1995 found that 68% of stents forgotten more than 6 months were calcified and 10% were fragmented. Multiple urologic procedures were necessary to remove the stones. Long-term effects of these forgotten stents may lead to voiding dysfunction and renal insufficiency. Schlick, et al., 1998 are developing a biodegradable stent that will preclude the need for stent removal.

Encrustation

The urinary system presents a challenge because of its chemically unstable environment. Long-term biocompatibility and biodurability of devices have been problems due to the supersaturation of uromucoids and crystalloids at the interface between urine and the device. Encrustation of ureteral stents is a well-known problem, which can be treated easily if recognized early. However, severe encrustation leads to renal failure and is difficult to manage (Mohan-Pillai et al., 1999). All biomaterials currently used become encrusted to some extent when exposed to urine.

The encrusted deposits can harbor bacterial biofilms. In addition, they can render the biomaterial brittle which causes fracture in-situ, a serious problem especially associated with the use of polyethylene and polyurethane ureteral stents (although silicone stents have also been reported to fracture). Stent fragments can migrate to the bladder or renal pelvis with serious repercussions.

Surface science techniques were used to study three stent types after use in patients. The stent type, duration of insertion and age or sex of the patient did not correlate significantly with the amount of encrustation (Wollin et al., 1998). However, it has been suggested that factors which affect the amount of encrustation include the composition or the urine, the type of invading and colonizing bacteria and the structure and surface properties of the biomaterial used (Gorman 1995). A low surface energy surface seems to resist encrustation compared with a high surface energy surface (Denstedt et al., 1998).

Many different types of stone can form in the urinary tract. Calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, uric acid and cystine stones are metabolic stones because they form as a result of metabolic dysfunction. They usually are excreted from the urinary tract. Struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate) and hydroxyapatite (calcium phosphate) are associated with infection (infection stones). These account for 1520% of urinary calculi. ESWL is used to break up the larger infection stones because they don't pass; recurrence of the problem occurs with incomplete removal. Infection stones can manifest as poorly mineralized matrix stones, highly mineralized staghorn calculi or as bladder stones which often form in the presence of ureteral stents. Urea-splitting bacteria colonize the surface and cause alkalinization of the urine, which lowers the solubility of struvite and hydroxyapatite, and they deposit on the surface. Bacterial biofilm associated with encrustation is a common clinical occurrence. (Gorman and Tunney, 1997). It has been suggested that prevention of bacterial colonization would prevent encrustation because of their ultimate responsibility for its formation (Bibby et al., 1995).

An in vitro model was developed that produces encrustation similar to those seen in vivo (Tunney et al., 1996a). An experiment was conducted to compare the encrustation potential of various ureteral stent materials. The long-term struvite and hydroxyapatite encrustation of silicone, polyurethane, hydrogel-coated polyurethane, Silitek and Percuflex were compared. All of the materials developed encrustation, however, it was found by image analysis that the rates of encrustation varied on the different materials. Silicone had less encrustation (69% at 10 weeks) compared to the other materials (1 00%) at the same time point (Tunney et al., 1996b). Continuous flow models have also been developed which are more representative of conditions in the upper urinary tract. They are discussed by Gorman and Tunney, (1 997). Efforts to reduce encrustation using new materials, smoother surfaces and hydrogel coatings have been attempted.

A hydrogel-coated C-flex stent (Hydroplus, Boston Scientific) was shown to have less epithelial cell damage and encrustation than other biomaterials and was recommended by the investigators for long-term use (Cormio, 1995). In addition, a poly(ethy1ene oxide)/polyurethane composite hydrogel (Aquavenem, J & J) resisted intraluminal blockage in a urine flow model compared with silicone and polyurethane (Gorman et al., 1997a). Another advantage with Aquavene is that it is rigid in the dry state, which facilitates insertion past obstructions in the ureter and becomes soft on hydration providing comfort (Gorman and Tunney, 1997). Gorman et al. (1997b) concluded that the chance of stent fracture would be reduced if the ureteral stent side holes were eliminated. Urinary tract infection is another common major problem with the usage of ureteral stents. Initially, a conditioning film is deposited on the ureteral stent surface. The film is made up of proteins, electrolyte materials and other unidentified materials that obscure the surface properties of the stent material. Electrostatic interactions, the ionic strength and pH of the urine and differences in fluid surface tensions affect bacterial adhesion to the conditioning film. Subsequently, a microbial biofilm forms over time. The biofilm is composed of bacterial cells embedded in a hydrated, predominantly anionic mixture of bacterial exopolysaccharides and trapped host extracellular macromolecules.

Obstruction

Obstruction of urine flow and urinary tract sepsis can result in continued growth of the biofilm. Colonization of devices implanted in the urinary tract can lead to dysfunction, tissue intolerance, pain, subclinical or overt infection and even urosepsis. Device related infections are difficult to treat and device removal is usually necessary. The biofilm has been found to impede the diffusion of antibiotics; in addition, the bacteria in the biofilm have a decreased metabolic rate , which also protects them against the effects of antibiotics (Wollin et al., 1998). Riedl, et al. (1 999) found 100% ureteral stent colonization rates in permanent and 69.3% in temporary stents. Antibiotic prophylaxis did not prevent bacterial colonization and it was recommended that it not be used. On the other hand, Tieszer, et al. (1 998) believe that fluoroquinolones can prevent infection. They also have found that some stents have denser encrustation than others, however, the stent material did not change the elements of the "conditioning film" adsorbed or alter its receptivity to bacterial biofilms.

Infection

The predictive value of urine cultures in the assessment of stent colonization was examined in 65 patients with indwelling ureteral stents. It was found that a sterile urine culture did not rule out the stent itself being colonized (Lifshitz, et al., 1999). Patients with sterile urine culture may benefit from prophylactic antibiotics; however, the authors contended that the antibiotics must work against gram-negative uropathogens and gram-positive bacteria including enterococci. It is obvious that there is controversy in the literature whether prophylactic systemic antibiotics are useful with ureteral stent implant. However, antibiotics do not seem to prevent stent colonization. Denstedt et al. (1998) have found that ciprofloxacin, with a 3 day burst every 2 weeks, actually is adsorbed onto the stent which makes longer term treatment possible with reduced risk of bacterial resistance. There has been research targeted at coating or impregnating urinary catheters with antimicrobials and products are on the market, however, there are no antimicrobial ureteral stents approved by the FDA.

The market need

It is clear that there is a need for a new material that will be able to resist encrustation and infection in the urinary tract. According to Merrill Lynch, ureteral stents represent an $80 MM US market. Boston Scientific is in the lead with ~50% of the market followed by Maxxim (Circon), Cook and Bard is a smaller player. There are a number of other small contenders.

The use of ureteral stents is increasing; the indications for ureteral stenting have broadened from temporary or permanent relief or ureteric obstruction to include temporary urinary diversion following surgical procedures such as endopyelotomy and ureteroscopy and facilitation of stone clearance after ESWL (Tolley, 2000).

The use of ureteral stents for patients having ESWL for renal calculi is however controversial and seems to be related to the size of the stones and invasiveness of the procedure. According to survey results reported by Hollowell, et al. (2000), there is a significant difference in opinion concerning the use of stents with ESWL.

The number of ureteral stents used in patients with stones 2 cm or less treated with ESWL is significant in spite of the lack scientific evidence in support of this practice. Of 1,029 urologists returning surveys, for patients with renal pelvic stones 10, 15 or 20 rnm treated with ESWL, routine stent placement was preferred by 25.3%, 57.1 % and 87.1 %, respectively. Urologists recommend using ureteroscopy rather than ESWL for distal ureteral calculi 5-1 0 mm.

Intellectual property

Search strategy

- Databases searched: US-G, US-A, EP-A, EP-B, WO, JP, DE, GB, FR

- Search scope: Title, Abstract or Claims

- Years: 1981-July 2008

- Search query: (ureter* OR urether* OR ureth* OR uretr*) AND (stent*) AND (*microb* OR *bacter*)

- Results: 177 patents (82 unique patent families)

Sample patents

| Patent | Assignee | Title | Abstract |

|---|---|---|---|

| US6468649 B1 | SCIMED LIFE SYSTEMS INC | Antimicrobial adhesion surface | The present invention provides an implantable medical device having a substrate with a hydrophilic coating composition to limit in vivo colonization of bacteria and fungi. The hydrophilic coating composition includes a hydrophilic polymer with a molecular weight in the range from about 100, 000 to about 15 million selected from copolymers acrylic acid, methacrylic acid, isocrotonic acid and combinations thereof. |

| US5554147 A | CApHCO, Inc. | Compositions and devices for controlled release of active ingredients | A method for the controlled release of a biologically active agent wherein the agent is released from a hydrophobic, pH-sensitive polymer matrix is disclosed and claimed. The polymer matrix swells when the environment reaches pH 8.5, releasing the active agent. A polymer of hydrophobic and weakly acidic comonomers is disclosed for use in the controlled release system. Further disclosed is a specific embodiment in which the controlled release system may be used. The pH-sensitive polymer is coated onto a latex catheter used in ureteral catheterization. A common problem with catheterized patients is the infection of the urinary tract with urease-producing bacteria. In addition to the irritation caused by the presence of the bacteria, urease produced by these bacteria degrade urea in the urine, forming carbon dioxide and ammonia. The ammonia causes an increase in the pH of the urine. Minerals in the urine begin to precipitate at this high pH, forming encrustations which complicate the functioning of the catheter. A ureteral catheter coated with a pH-sensitive polymer having an antibiotic or urease inhibitor trapped within its matrix will release the active agent when exposed to the high pH urine as the polymer gel swells. Such release can be made slow enough so that the drug remains at significant levels for a clinically useful period of time. |

| US20030153983 A1 | SCIMED LIFE SYSTEMS INC | Implantable or insertable medical device resistant to microbial growth and biofilm formation | Disclosed are implantable or insertable medical devices that provide resistance to microbial growth on and in the environment of the device and resistance to microbial adhesion and biofilm formation on the device. In particular, the invention discloses implantable or insertable medical devices that comprise at least one biocompatible matrix polymer region, an antimicrobial agent for providing resistance to microbial growth and a microbial adhesion/biofilm synthesis inhibitor for inhibiting the attachment of microbes and the synthesis and accumulation of biofilm on the surface of the medical device. Also disclosed are methods of manufacturing such devices under conditions that substantially prevent preferential partitioning of any of said bioactive agents to a surface of the biocompatible matrix polymer and substantially prevent chemical modification of said bioactive agents |

Phase 2: Deeper Dive

Scenario

Client wishes to acquire a ureteral stent company. Dolcera provides the following Design History File (DHF) review.

Design History File Review: Review components

| Review | Verification | Tasks | Expertise |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design Input | Design input documents for sufficiency |

|

Quality systems |

| Design input documents linked to the product performance specifications |

| ||

| Product Performance Specifications (PPS) | Design inputs correlate adequately to the specifications; DV&V (design verification and validation) criteria are based on risk management documentation or if the criteria are based on sound statistical sampling plans |

|

Quality systems, CAD |

| Appropriate design verification and validations (DV&V) are performed |

| ||

| Product performance specifications correspond to appropriate design output documents |

| ||

| Risk Management Documents | Risk Analysis, Design Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (DFMEA), Process FMEA, other risk management documentation |

|

Quality systems |

| DFMEA links appropriately to the PPS |

| ||

| Appropriate DV&V reports and design output documents are referenced correctly as risk mitigation activities in the DFMEA |

| ||

| PFMEA links appropriately to the process validation protocol acceptance criteria; In-process inspection procedures and/or manufacturing procedures are recorded as appropriate risk mitigation activities in the PFMEA |

| ||

| Design Output Documents | Completeness of drawings |

|

Quality systems, CAD |

| Correlate First Article Inspection data to the dimensions on the drawings |

| ||

| Manufacturing Documents | Manufacturing procedures, component specifications, raw material specifications, incoming and in-process inspection procedures for completeness |

|

Material science, manufacturing engineering, quality systems |

| Linkage between component and raw material specifications and appropriate incoming inspection procedures |

| ||

| Inspection procedures have adequate sampling plans based on PFMEA risk mitigation levels – this includes packaging and labeling materials |

| ||

| Calibration records and preventive maintenance records; in-process / incoming inspection test methods and related test method validations |

| ||

| Validation Report | DV&V reports, Shelf-life reports, Biocompatibility test reports, Sterilization reports, Packaging Validation reports, Process Validation Reports |

|

Quality systems |

| Design test methods and related test method validations |

|

Sample report

Performance/Functional Characteristics

| Design Input | Design Output | Design Verification Report # | Status (P/F/R) | Design Validation Report # | Status (P/F/R) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| User Needs | User Need Rationale | Engineering Specification | Engineering Specification Rationale | |||||

| Provide antimicrobial resistance for up to 2 weeks | Ureteral Stent User Survey (Document #XXXXX) | Stent must have chlorohexadine surface concentration of 10-20 mg/cm2 for 3 weeks | Document #XXXXX | Test Document #XXXXX | Report 01-005-06-007 | P | Report 01-005-06-007 | P |

Potential DHF Review Outcomes

Based on a review of the above DHF documents a potential outcome for the uretral stent acquisition project could involve the following:

- Better explanation of existing design input documents and also better linkage between the design inputs and product specifications.

- Creation of some new test methods for design, incoming and in-process inspections and also include recommendations for the test method validations. Creation of any new DV&V data would be highly unlikely as it could potentially trigger a new submission or a note-to-file to the regulatory agencies.

- Change in raw materials to better grade materials e.g. Switching resin to a USP Class VI biocompatible resin. This would eliminate some on-going testing but require additional upfront one time biocompatibility testing.

- Updating drawings based on results from the FAI data.

- Converting existing Company Y documents into Company X format and identifying potential gaps and streamlining linkage between raw material specifications and inspection procedures.

- Identifying installation, operational and process qualification requirements with the assumption that no additional design verification and validation activities are required based on the fact that the device is currently approved for sale in the US and ROW.

- Recommend activities necessary for completing packaging, labeling, ship testing and shelf-life testing. Stress should be on being able to leverage existing data for shelf-life without changing the regulatory status of the device.

- Company X may want to perform additional biocompatibility testing to create an internal baseline and also update their biocompatibility files.

- Help streamline suppliers for components when switching over from Company Y to Company X. Search for existing Company X suppliers that can supply off the shelf items that Company Y may be sourcing from other vendors / suppliers.

- Identify process improvements that can be rolled into the manufacturing transfer without changing the design and impacting the existing regulatory status for the device e.g. instead of hand mixing pigment to resin use a pre-mixer to control quality of mixing and resulting extrusion or perform the molding and over-molding steps in 1 machine instead of 2 separate molding machines.

Phase 3: Post-acquisition integration

Deadlines

Goal: Switch production transparently to new facilities transparently to the distribution system

| Stage | Tasks | Milestone payment | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design center integration plan |

|

September 15, 2008 | |

| Design to manufacturing transfer | December 15, 2008 | ||

| Equipment transfer | Milestone I payment | Jan 7, 2009 | |

| Shut production at acquiree facility | Negotiation for contract extension | Milestone II payment | Feb 15, 2009 |

| Start production in acquirer facility | Feb 7, 2009 | ||

| Switch to new SKU | Feb 15, 2009 | ||

| End development of new generation product/s in old facility | Feb 7, 2009 | ||

| Restart development of new generation product/s post-acquisition | Final milestone payment | Mar 1, 2009 |

Documents and Ownership

| Document | Owner | Last update date |

|---|---|---|

| Product performance specifications | Paul Swain | 07/27/2008 08:15:35 PST |

| Component specifications | Kevin Teller | 06/12/2008 12:22:07 PST |

| Preclinical test results | Joanne Krannert | 07/03/2008 14:17:00 PST |

| Clinical tests | Joanne Krannert | 08/01/2008 08:00:55 PST |