Ureteral Stent: Concept

An antimicrobial ureteral stent, which inhibits encrustation and bacterial colonization while maintaining patient comfort.

- Ureteral stent: resists migration, resists fragmentation, is kink resistant and radiopaque.

- Bacterial colonization: antimicrobial activity for up to two weeks.

- Patient Comfort: stent has a low coefficient of fiiction (value) for ease of insertion and will soften on implant at body temperature to maintain patient comfort.

Background

Ureteral stents are used in urological surgery to maintain patency of the ureter to allow urine drainage from the renal pelvis to the bladder. These devices can be placed by a number of different endourological techniques. They are typically inserted through a cystoscope and may also be inserted intraoperatively. Indwelling ureteral stents help to reduce complications and morbidity subsequent to urological and surgical procedures. Frequently, ureteral stents are used to facilitate drainage in conjunction with Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL) and after endoscopic procedures. They are also used to internally support anastomoses and prevent urine leakage after surgery. Ureteral stenting may almost eliminate the urological complications of renal transplantation.

The advent of ESWL and the more recent barrage of endourological techniques have increased the indications for ureteral stents (Candela and Bellman 1997). Indications for use include:

- Treatment of ureteral or kidney stones

- Ureteral trauma or stricture

- Genitourinary reconstructive surgery

- Hydronephrosis during pregnancy

- Obstruction due to malignancy

- Retroperitoneal fibrosis

The need for ureteral stents range from a few days to several months. For patients with serious urological problems, ureteral stent maintenance may become a life-long necessity. Unfortunately, there are many problems associated with using ureteral stents.

Ureteric stenting difficulties

| Common | Rare |

|

|

Today, elastomeric materials, such as silicones, polyurethanes and hydrogel-coated polyolefins are used, with no clear winner, which can withstand the urinary environment.

- Although silicone has better long-term stability than other stent materials, its extreme flexibility makes it difficult to pass over guidewires and through narrow or tortuous ureters.

- Polyethylene is stiffer and easier to use for patients with strictures; however, it has been known to become brittle with time leading to breakage and is no longer commercially available. * Polyurethane has properties that fall in between polyethylene and silicone; however, stent fracture also has been an issue with polyurethanes.

Attempts have been made to develop polymers with a combination of the best of all properties. The key players are C-Flex (Concept Polymer Technologies), Silitek and Percuflex (Boston Scientific).

- C-Flex is proprietary silicone oil and mineral oil interpenetrated into a styrenelolefin block copolymer with the hope of reduced encrustation.

- Silitek (Medical Engineering Corporation) is another silicone-based copolymer.

- Percuflex is a proprietary olefinic block copolymer.

Metallic stents have been used recently to treat extrinsic ureteric obstructions. The effect of synthetic polymers on the urothelium of the urinary tract seems to be dependent on the bulk chemical composition of the polymer, the chemical composition of its surface, coatings on the device surface, smoothness of the surface and coefficient of friction.

Typically, most ureteral stents are made of relatively smooth catheters. Koleski et al., (2000) tested a longitudinally grooved ureteral stent made by Circon in the pig ureter. The results indicated that the grooved stent led to better drainage than a conventional stent. Their opinion is that the ureter wall has a better chance of collapsing over a smooth surface than a grooved surface, especially when debris is present. Stoller (2000) had the same experience with the SpiraStent(Urosurge Corp.). This helical stent was superior at passing stones than a conventional smooth stent.

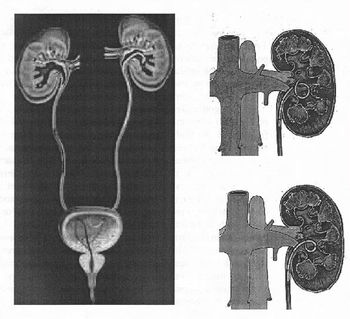

There are a variety of ureteral stent configurations with different anchoring systems. Most stents today have a double pigtail anchoring system. (Tolley, 2000), Dunn et al, (2000) conducted a randomized, single-blind study comparing a Tail stent (proximal pigtail with a shaft which tapers to a lumenless straight tail) to a double pigtail stent. The Tail stent was found to be better tolerated than the double-pigtail concerning lower urinary tract irritative symptoms. A double-J ureteral stent and a flexible ureteropyeloscope are shown in the first diagram. The other two diagrams show a pigtail ureteral stent in place; the end of the pigtail is facing away fiom the ureteral opening in the second of these two diagrams.