Patent Eligibility Post-Alice

Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International was a 2014 decision of the US Supreme Court on patent eligibility. The issue was whether certain claims about a computer-implemented, electronic escrow service for facilitating financial transactions covered abstract ideas ineligible for patent protection. The patents were held to be invalid because the claims were considered to be based on abstract idea, and implementing them on a computer was not enough to make the idea a patentable subject matter.

This case was widely considered as a decision on software patents or patents on software for business methods.

Background

Alice Corporation had four patents on electronic methods for financial-trading systems on which trades between two parties who are to exchange payment are settled by a third party in ways that reduce settlement risk. CLS Bank International and CLS Services Ltd. were allegedly using similar technology. Alice accused CLS Bank of infringement of Alice’s patents, CLS Bank filed suit against Alice in 2007, seeking a declaratory judgment that the claims at issue were invalid. Alice counterclaimed, alleging infringement.

Litigation

The district court stated that a method “directed to an abstract idea of employing an intermediary to facilitate simultaneous exchange of obligations in order to minimize risk” is a “basic business or financial concept,” and that a “computer system merely configured to implement an abstract method is no more patentable than an abstract method that is simply electronically implemented.

The Supreme Court observed that an abstract idea could not be patented just because it is implemented on a computer. In Alice, a software implementation of an escrow arrangement was not patent eligible because it is an implementation of an abstract idea. Escrow is not a patentable invention, and merely using a computer system to manage escrow debts does not rise to the level needed for a patent. Under Alice, the “Mayo framework” should be used in all cases in which the Court has to decide whether a claim is patent-eligible.

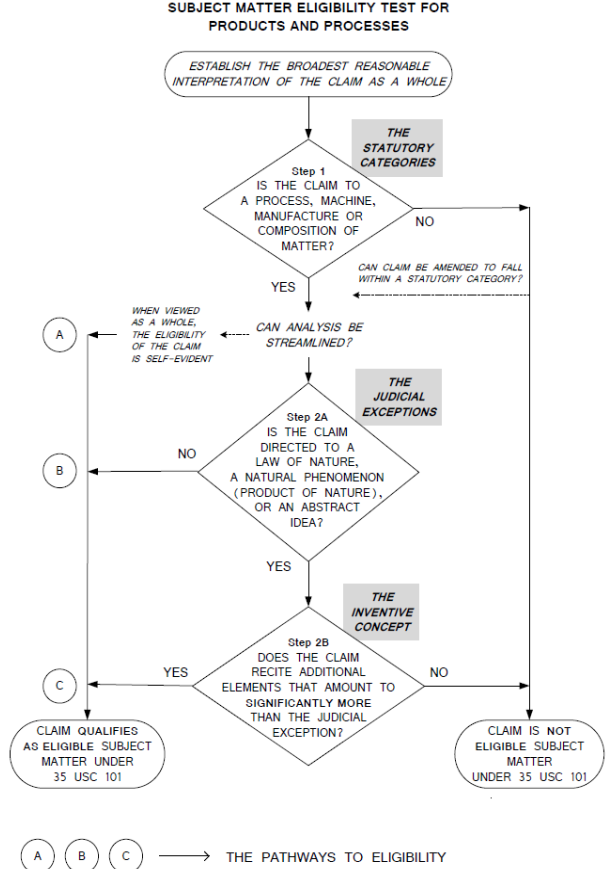

The Court held that Mayo explained how to address the problem of determining whether a patent claimed a patent-ineligible abstract idea or instead a potentially patentable practical implementation of an idea. This requires using a “two-step” analysis:

- Whether the patent claim under examination contains an abstract idea, such as an algorithm, method of computation, or other general principle. If not, the claim is potentially patentable, subject to the other requirements of the patent code. If the answer is affirmative, the court must proceed to the next step.

- Whether the patent adds to the idea “something extra” that embodies an “inventive concept.”

If there is no addition of an inventive element to the underlying abstract idea, the court should find the patent invalid under § 101. This means that the implementation of the idea must not be generic, conventional, or obvious, if it is to qualify for a patent.

Supreme Court did not offer the clearest guidance on when a patent claims merely an abstract idea, but it did offer guidance that should help to invalidate some of the more egregious software patents out there.

Subsequent developments

Alice decision had a dramatic effect on the validity of software patents and business-method patents. After Alice decision, these patents suffered a very high mortality rate. Hundreds of patents were invalidated under §101 of the U.S. patent laws.

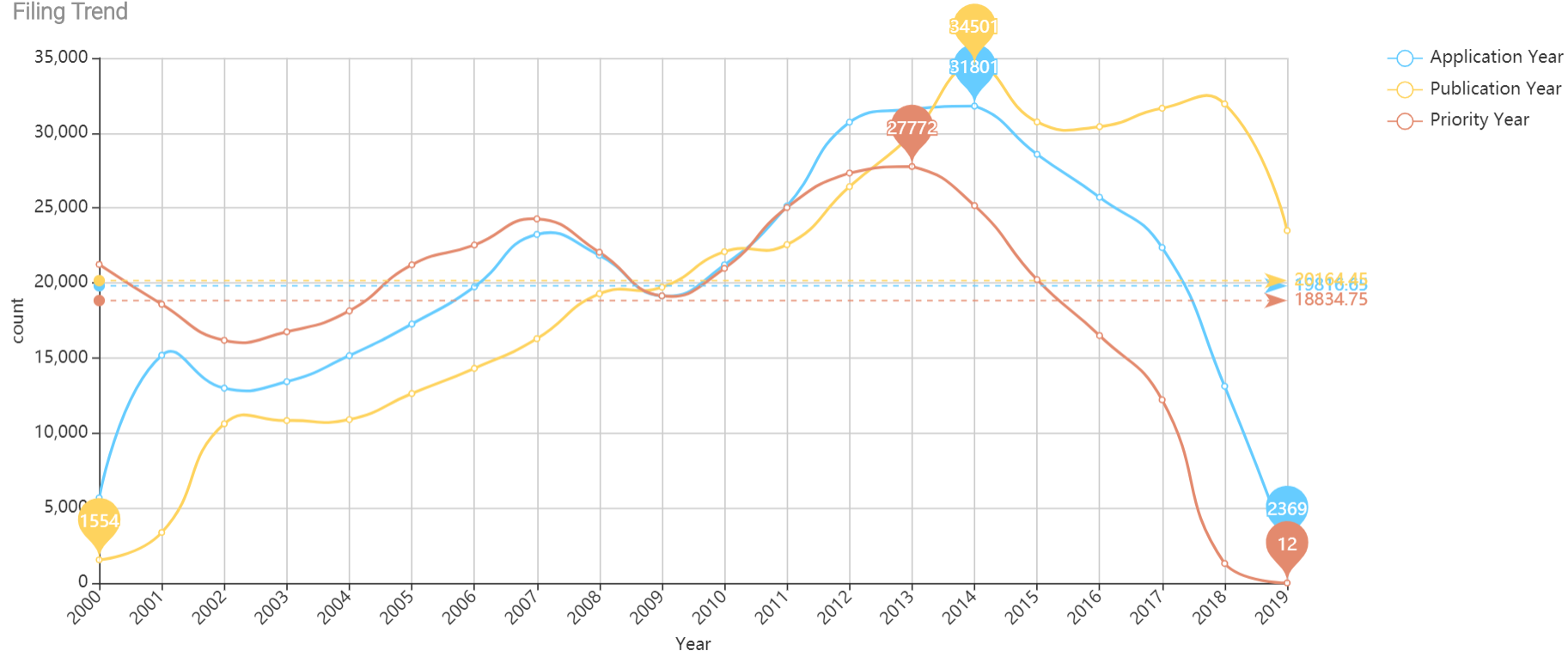

Patent issuance statistics from the PTO showed a significant drop in the number of business method patents issued following the Alice decision.

Figure: Business method Patents filling trends – Comparison on PCS (AI enabled Analytics tool from Dolcera)

Recent developments

USPTO recently provided new guidance as to how it is going to address and analyze subject matter eligibility under 35 U.S.C. §101 and how it will apply 35 U.S.C. §112 to computer-implemented inventions.

Chances of avoiding invalidity under Section 101/Alice can be improved by clearly identifying a technological problem and by providing a detailed description of a technological solution. The description of a technological solution involves describing the functionality of the invention and how the functionality is carried out.

The Section 112 guidance focuses on the need to provide sufficient technical detail related to the implementation of a claimed function and how an intended outcome or solution is accomplished.

According to the guidance: for interpreting a claim term under 35 U.S.C. § 112(f) “examiners should check whether: (1) the specification provides a description sufficient to inform one of ordinary skill in the art that the term denotes structure; (2) general and subject matter specific dictionaries provide evidence that the term has achieved recognition as a noun denoting structure; and (3) the prior art provides evidence that the term has an art-recognized structure to perform the claimed function.”

When a claim term is interpreted as a means-plus-function limitation, the specification must disclose components and/or algorithm for performing the function, or else the claim may be indefinite under 35 U.S.C. § 112(b).

The guidance states for satisfying the written description requirement under Section 112(a), “the specification must describe the claimed invention in sufficient detail such that one skilled in the art can reasonably conclude that the inventor had possession of the claimed invention at the time of filing. For instance, the specification must provide a sufficient description of an invention, not an indication of a result that one might achieve.”

“Abstract ideas” can be synthesized to fall into the following three categories:

- Mathematical concepts like mathematical relationships, formulas, and calculations.

- Certain methods of organizing human interactions, such as fundamental economic practices; commercial and legal interactions; managing relationships or interactions between people; and advertising, marketing, and sales activities.

- Mental processes, which are concepts performed in the human mind, such as forming an observation, evaluation, judgment, or opinion.

English

English